Environmental Enrichment

Our first blog post of the 3 R’s series introduced Refinement of husbandry practices using our animal well-being assessment framework. To meet the goals of ensuring animals have access to basic needs, species-typical behaviors, agency, and joy, we use environmental enrichment to fill any gaps we identify.

What is “environmental enrichment”? Below are two definitions that capture the goals of environmental enrichment.

“Environmental enrichment is an animal husbandry principle that seeks to enhance the quality of captive animal care by identifying and providing the environmental stimuli necessary for optimal psychological well-being. In practice, this covers a multitude of innovative, imaginative, and ingenious techniques, devices, and practices aimed at keeping captive animals occupied, increasing the range and diversity of behavioral opportunities, and providing a more stimulating and responsive environment” (Forthman & Seidensticker 1998).

“Enrichment is a dynamic process for enhancing animal environments within the context of the animal’s behavioral biology and natural history. Environmental changes are made with the goal of increasing the animal's behavioral choices and drawing out their species-appropriate behaviors, thus enhancing animal welfare” (1999 AZA Behavior Scientific Advisory Group).

With an understanding of what environmental enrichment means, let’s dive into how we ensure we are providing sufficient environmental enrichment.

Considered the father of environmental enrichment, Dr. Hal Markowitz dedicated his life to creating environments that empower animals to control their own feeding schedules. Dr. Markowitz emphasized that clear goals, along with rigorous data collection, are essential to gauging efficacy of enrichment programs (Bender and Strong 2019).

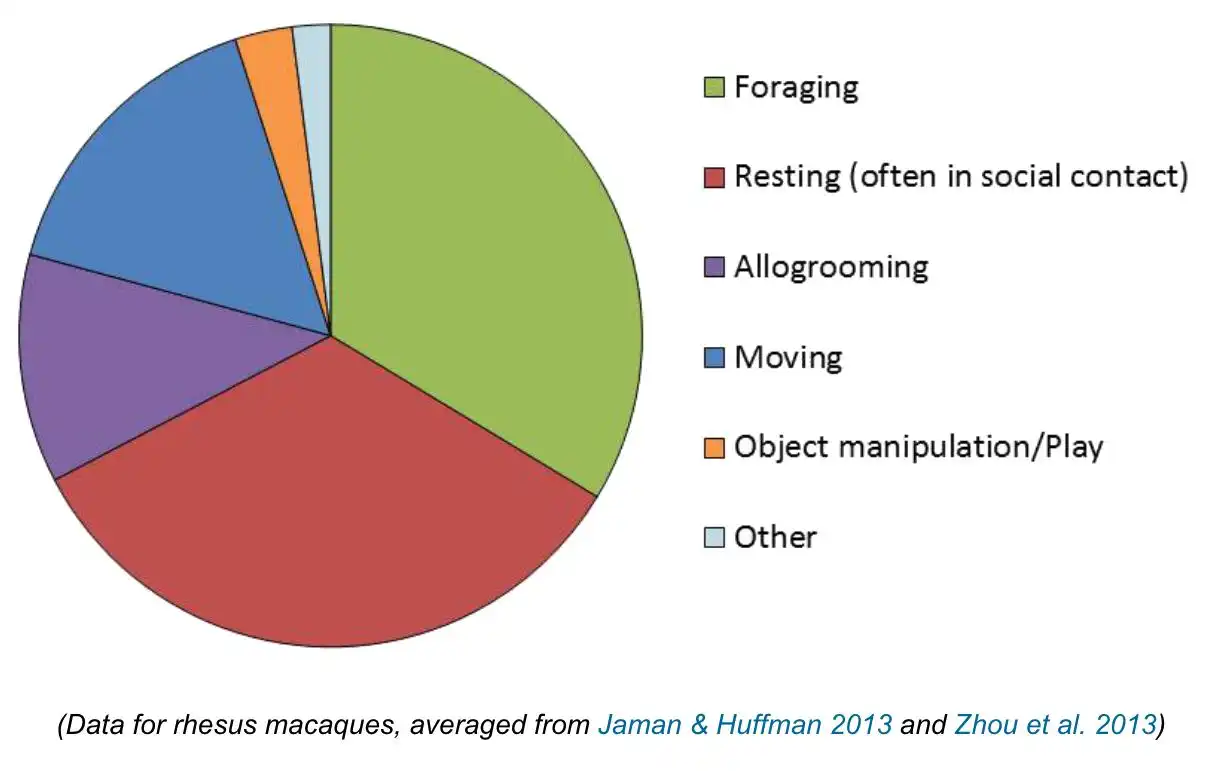

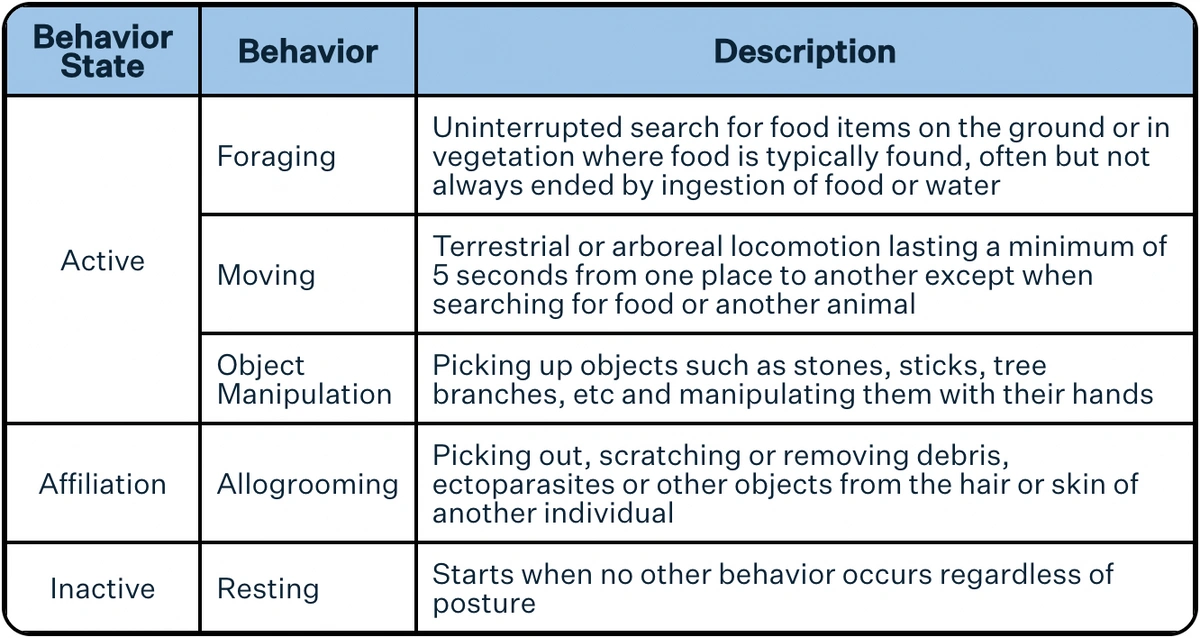

Using Dr. Markowitz’s methodology, we approach our enrichment program through a first principles lens by comparing our animals’ time spent in each activity with their counterparts in the wild. We call these changes in behavioral states that an individual makes throughout the day “activity budgets”. From there, we can identify any behavioral differences between an animal in our care and those in the wild and provide enrichment that satisfies those essential species-typical behaviors. He believed ethograms - tables that define a list of behaviors that a particular animal species displays - should be used to guide zoos’ enrichment plans.

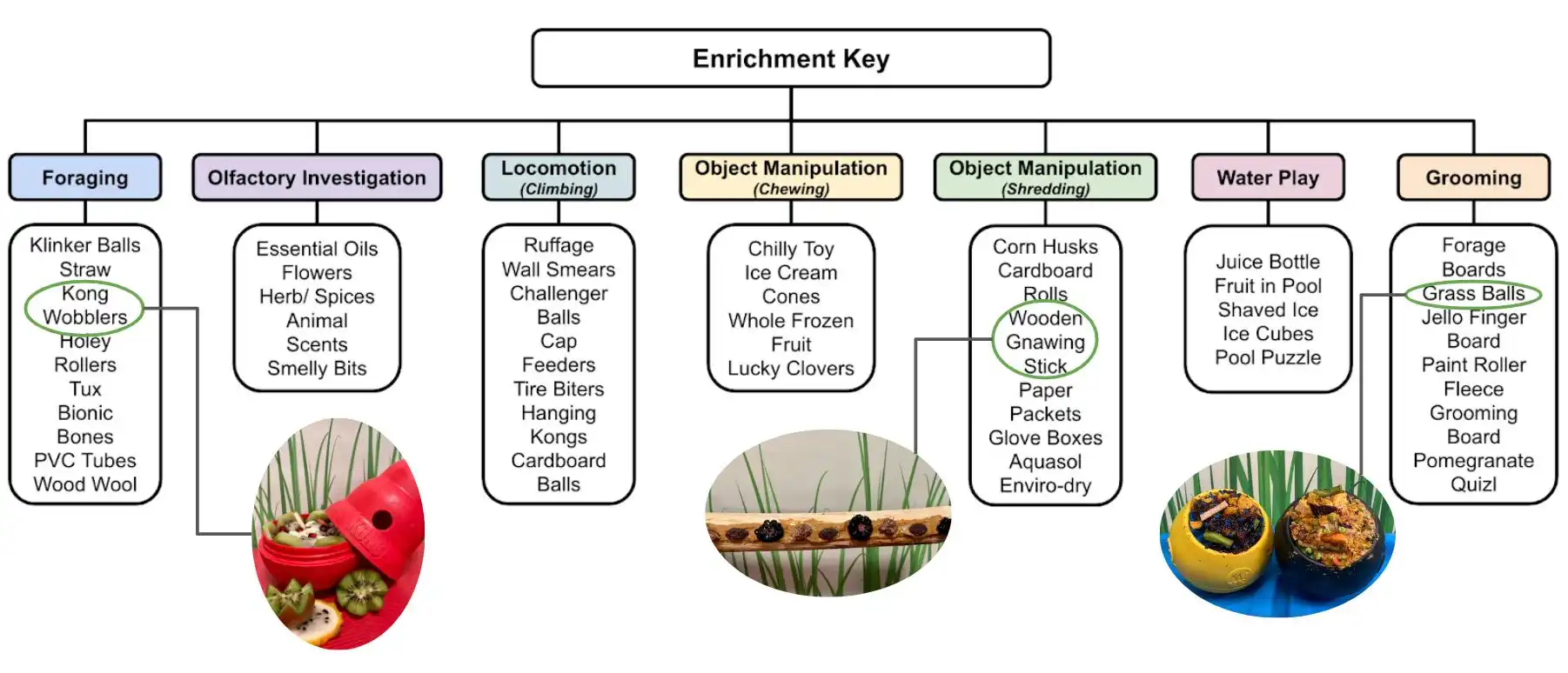

Traditionally, in the animal care industry - especially animals in a captive environment such as zoos, sanctuaries, and laboratory facilities - enrichment is used to decrease stereotypies, or abnormal behaviors. However, the presence of abnormal behaviors indicates that something may be lacking in an animal’s environment, as wild animals in their fully enriched natural habitat do not typically exhibit abnormal behaviors. Accordingly, our philosophy is to allow animals to safely and easily access their full range of natural species-typical behavior as a minimum obligation of animal caretakers. The goal of enrichment should instead be to exceed that basic care by offering a wide range of interesting ways to cognitively stimulate animals and to give them a variety of choices about how to engage in those behaviors. Figures 1-3 show examples of structural enrichment and foraging devices used to maximize cognitive stimulation throughout our animals’ day.

Since Dr. Markowitz’ early work in this field, enrichment programs across the country have developed frameworks based on his original teachings. At Neuralink, we adopted Disney’s Animal Kingdom S.P.I.D.E.R. framework to determine enrichment needs in our facilities. We chose the S.P.I.D.E.R. framework because it organizes the process in a coherent, first principles fashion, and highlights the importance of species-typical as well as individual behavioral needs as the fundamental guide to enrichment development.

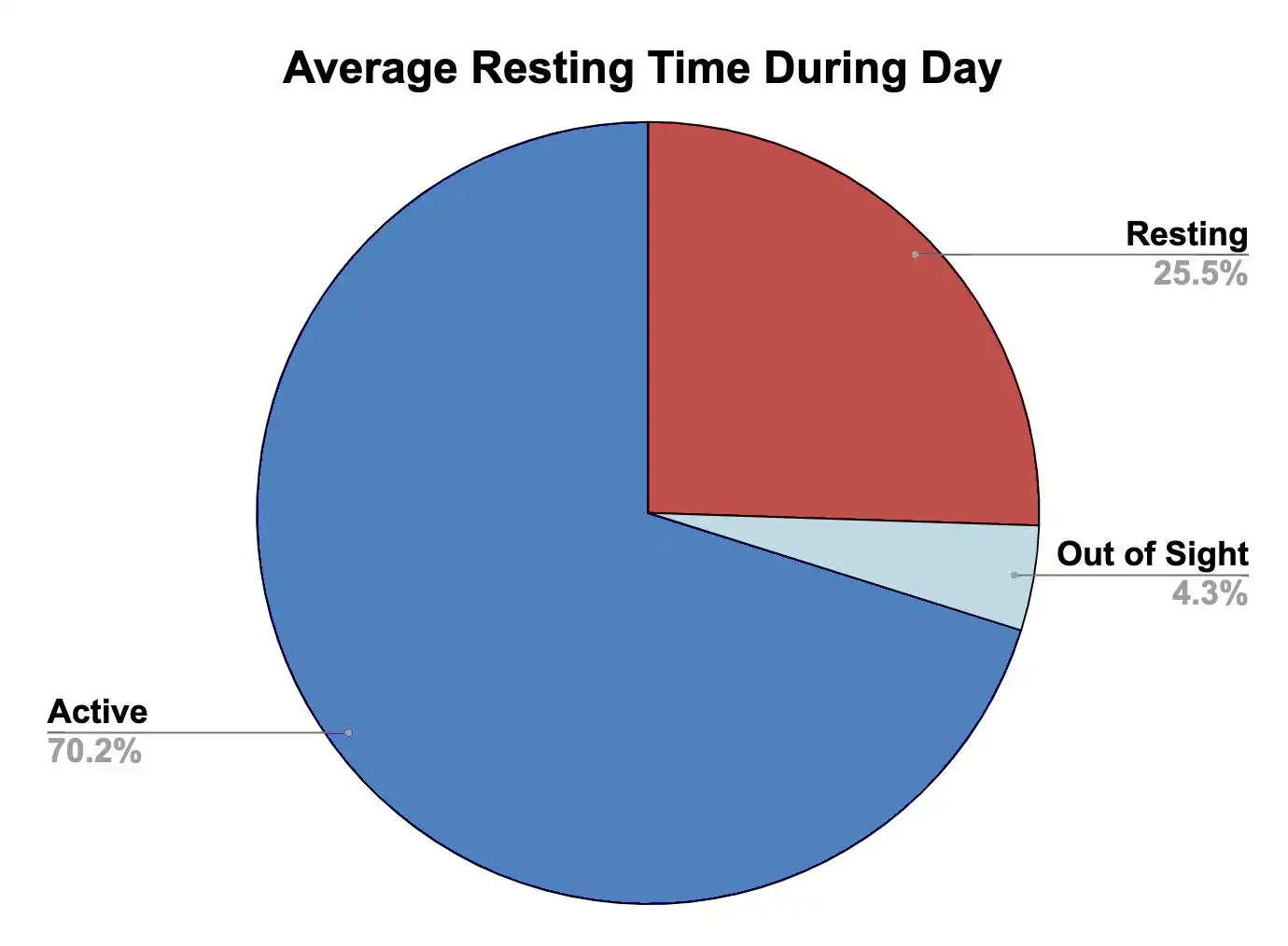

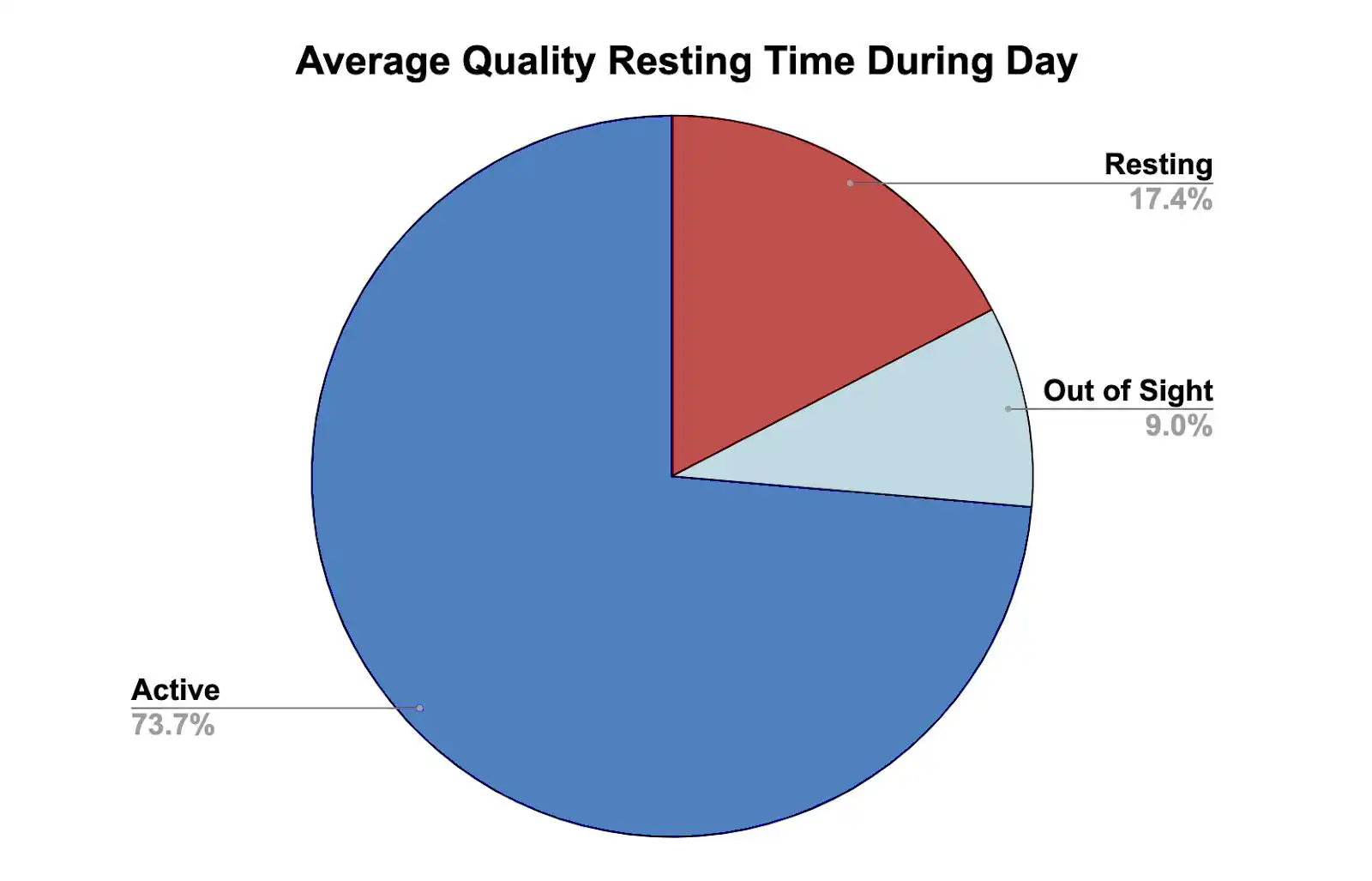

Below, we go through an example of how we used the S.P.I.D.E.R. framework to target increased resting behavior in Rhesus macaques. As shown in Fig. 4, our macaques demonstrate comparable results to their wild counterparts in the amount of time they rest throughout their 12 hour day.

Setting Goals

To identify behaviors to promote through environmental enrichment in our Rhesus macaques, we looked at the activity budget of their wild counterparts. We learned that wild macaques spend about one-third of their day resting and wanted our animals to have similar resting patterns when designing our vivarium. To accurately compare the activity budget of our animals versus their wild conspecifics observed in Fig. 5, we started by using the same ethogram definition of resting that Jaman & Huffman used for wild counterparts (Fig. 6). This allowed us to confirm that our animals' average time resting closely matched that of wild counterparts under the definition used by wildlife scientists. However, it made us wonder if the definition afforded our animals enough quality of rest. Thus, we decided to set our enrichment goal to ensure access to quality rest.

Planning

Once we determined the species-typical behaviors we wish to promote (quality rest), we considered potential safety concerns, resources needed to access these behaviors, and where/ when the enrichment will take place. We determined that we needed to give animals plenty of space to interact safely with a conspecific and also provide highly desirable resting spots. We also needed to ensure animals felt comfortable enough to fully relax.

We started by researching what a relaxing environment for a macaque might look like in a natural environment. Resting areas for Rhesus macaques in the wild are usually either on the ground or up in trees depending on whether predators are present in the environment. Macaques typically take shelter at higher altitudes in the colder months and lower altitudes during warmer months to minimize energy expended through thermoregulation. They also tend to rest in grasslands, on rocks or fallen trees, and nearby forage patches where they last foraged for resources each day (Tsuji 2011).

In response, we designed environments that allowed enough space for safe socialization with a social partner and with non-grated, non-metal, thermoregulated perches, warm bedding, and hanging fabric-based hammocks such as the one shown in Fig. 7. Our goal was to create a comfortable sleeping environment that would withstand the strength and curiosity of a macaque in addition to more closely mimicking materials they sleep on in the wild.

Implementation

For the next step, we created an enrichment schedule that focused on animals receiving structural enrichment in their homes that support the performance of species-typical behaviors such as foraging, object manipulation, moving, and resting. Because the key to enrichment is novelty, we rotate these structures regularly to diversify the animals’ environment. Through our icon program described in a recent blog post, our animals can exercise agency by also selecting their preferred structural enrichment.

To specifically encourage resting, we incorporated a number of different hammocks, buckets, perches, swings, and tires that give animals plenty of choice of where to snuggle up and take a nap. We’ve also experimented with various foraging substrates to incorporate more nesting material that increases comfort (Fig. 8 - 10).

Mars interacts with his straw foraging substrate.

Documentation and Evaluation

We use an enrichment approval form to manage the submission, assessment, and approval of any new enrichment item. Any Neuralink employee can submit an enrichment approval form. Our veterinarians examine each item submitted and may suggest modifications for optimal safety.

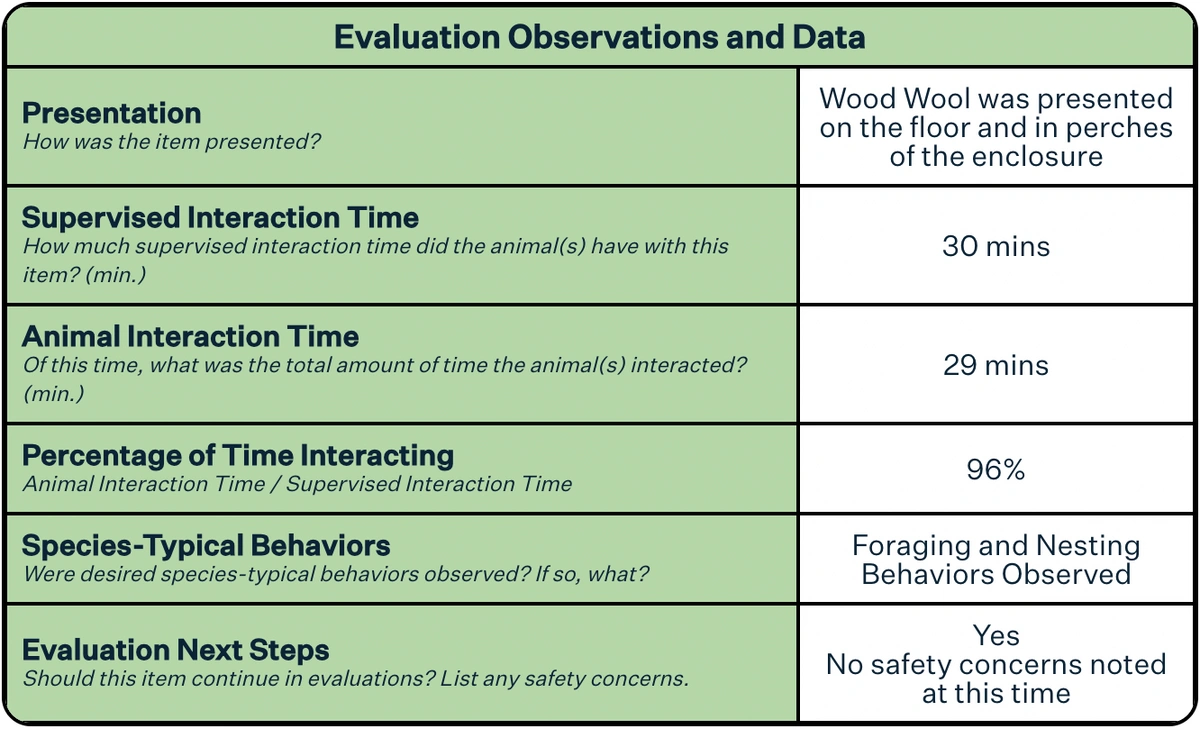

In January, an animal caretaker submitted the idea to use wood wool as a nesting material for our Rhesus macaques (Fig. 11). After the item was assessed and approved, we documented engagement levels to make sure the novel enrichment truly met our cognitive engagement goals, targeted the desired behavior, and posed no health / safety risks for the animal (Fig. 12).

The importance of continuously evaluating environmental enrichment is highlighted in the book Canine Enrichment for the Real World by Allie Bender and Emily Strong. In the book, the authors discuss Dr. Markowitz’ thoughts on the impact of confirming that the intended enrichment is in fact enriching the lives of animals.

“Dr. Markowitz understood that it was important, however, to not just think and feel that enrichment was helping zoo animals, but to conclusively and unquestioningly know. After all, enrichment is about quantifiably improving the quality of life of captive and domesticated animals, which means that it isn’t enough for enrichment to look good or feel good to us. Enrichment isn’t about us; it’s about the animals’ well-being” (Bender and Strong 2019).

To date, this substrate doesn’t pose any safety concerns (e.g., excessive consumption), holds up to our drainage system, and shows positive engagement. We also observed our macaques making nests with it. For these reasons, the new enrichment passed with flying colors. Now that the evaluation period is complete, we’ve added wood wool to our regular enrichment rotation, helping to fill that necessary gap to target increased amounts of resting behavior.

To make sure we’ve actually met our goal of increasing the amount of time our macaques spend resting throughout the day, we conducted behavior scans on our primates using the definition found on the ethogram in Fig. 6. Using behavior scans, we can reliably ascertain information about their resting patterns. With this data, we found that our animals spend about 25.5% of their day time resting (Fig. 4).

Re-Adjustment

We regularly reassess which enrichment works best, as well as confirm that the stimuli provided remains novel enough to continue to engage the animal. We were excited to find that we accomplished our goal of more closely mimicking a wild macaque’s activity budget, but we still wanted to gain more insight on the quality of their rest throughout the day.

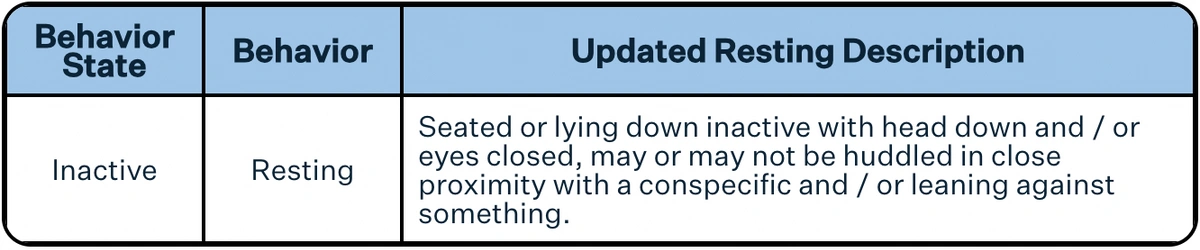

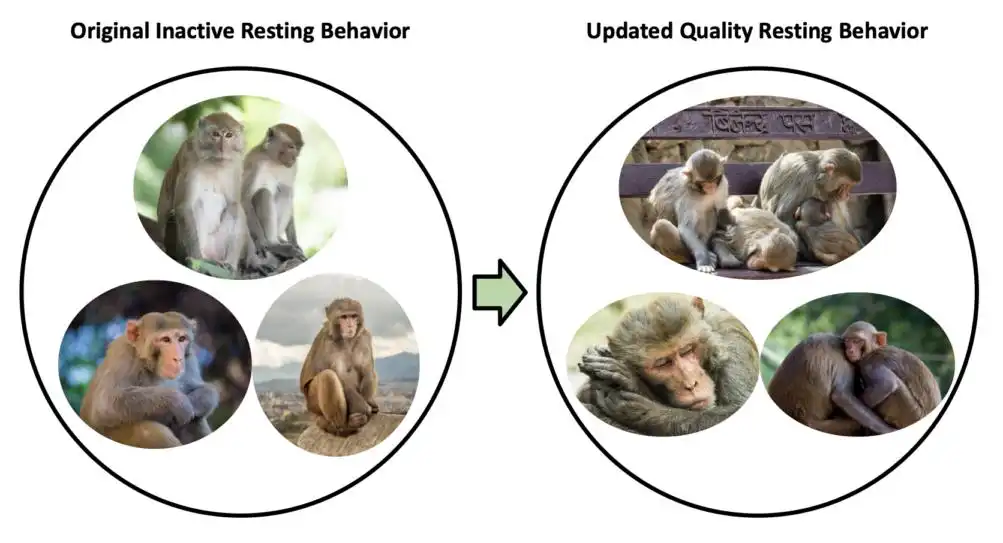

As discussed above, we initially started by using the same ethogram definition of resting that Jaman & Huffman used for wild counterparts. To exclude inactive states where animals are not moving but may not truly be relaxed, we modified our definition of resting to the one in the table below (Fig. 13). Because we can’t tell whether animals are truly sleeping without more invasive interventions, our updated definition of resting includes the animal having their head down and/ or eyes closed to indicate that they were likely napping.

When we evaluated behavior using this new resting definition, we found that animals spent around 17.4% of their day in a relaxed, high quality resting position (Fig. 15). It was expected that this number would be lower than our initial percentage that captured inactive behavior since we were using more stringent criteria than those used on Jaman & Huffman’s ethogram (pictures of the two different behavior definitions are displayed in Fig. 14).

It was encouraging to find that our animals felt comfortable in this relaxed state during the day while researchers and caretakers engaged with the animals, especially since this is not a behavior typically targeted in animal research environments. We are hoping to increase this even more by continuing to develop new environmental enrichment in the coming months.

We look forward to continuing the discussion in future blog posts about how we’ve encouraged this behavior in other areas of our program, such as building trust banks and using predictable schedule programs that make resting during the day feel safe for our animals.

Conclusion

Environmental enrichment helps us fill gaps identified in our well-being assessments. Increasing our total resting behavior duration is just one example of how we’ve used this S.P.I.D.E.R. framework. Utilizing this process, we’ve developed a supplemental enrichment program that encourages animals to increase performance of various species-typical behaviors throughout the week (Fig. 17).

We will continue to expand this program as we find more opportunities to enrich the lives of our animals each day. The S.P.I.D.E.R. framework allows us to think critically about future housing features that promote natural behaviors of each of the species living in our care. Stay tuned for our upcoming Refinement blog posts, where we’ll discuss how we motivate our animals to voluntarily participate in husbandry, veterinary medicine, and research behaviors through our animal training and behavior program.